It's Not Just a Movie, It's a Revelation (About the Audience)

IT is only a movie, and now that the reviews are in, one that is very unlikely to get a Best Picture nomination.

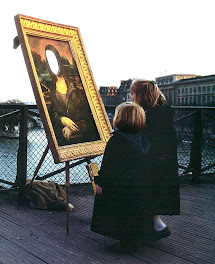

"The Da Vinci Code" has bombed with most critics, and could bomb with audiences that are not "Da Vinci" diehards. In it, a murder in the Louvre leads two sleuths to uncover a conspiracy by the Roman Catholic Church to hide the truth that Christianity as we know it is a lie. Even Tom Hanks, the lead actor, called the plot "scavenger-hunt-type nonsense." But it is doubtful the uproar will disappear.

The reason is that "The Da Vinci Code" is, in the sweep of Christian history, a historical marker — encapsulating in one muddled movie an era in which many Christian believers have assimilated a whole lot of new and unorthodox ideas, as well as half-truths and conspiracy thinking, into their faith, while still seeing it as Christianity. Call it Da Vinci Christianity.

"I'm definitely a Christian — I would label myself a Gnostic Christian," said Cliff Jacobs, 52, deputy executive director at Queens Public Television, as he left a screening of "The Da Vinci Code" Thursday night. He was referring to early Christians known as Gnostics, many of whom rejected the divinity of Jesus, but who left behind gospels that resurfaced in the last 60 years.

"I don't need someone to interpret God for me," Mr. Jacobs said. "When I want to commune with others, I go to church."

Maria Bolden, 42, a customer service representative for a cable company, said after seeing the movie, "If marriage is such a sacred sacrament, why is it such a problem for Jesus to have married?"

It is not that everyone has swallowed whole the story's sexiest heresy — that Jesus married his favorite apostle, Mary Magdalene, and fathered a line of royal offspring who still live today in France. It is that "The Da Vinci Code" reinforces doubts that some modern Christians already have about the origins of the Bible and the authenticity of the Jesus story.

The doubts did not originate with "The Da Vinci Code." Instead, the book plays off of popular interest in new discoveries like the Gnostic gospels, in feminist spirituality, and in the pagan roots of Christian traditions (for example, Easter as originally a fertility rite — why else the eggs and the bunnies?).

"The Da Vinci Code" also bolsters popular conspiracy theories about the Roman Catholic Church's power and propensity for cover-ups, an assumption that the church itself reinforced with its lack of transparency in handling cases of sexual abuse by priests.

"The Catholic Church has hidden a lot of things — proof about the actual life of Jesus, about who wrote the Bible," said Ricardo Henriquez, 25, the associate director of a senior center in the Bronx, as he waited for the Da Vinci screening to begin. "All these people — the famous Luke, Mark and John — how did they know so much about Jesus' life? If there was a Bible, who created it and how many times has it been changed?"

Mr. Henriquez, by the way, is a Catholic who was baptized and confirmed in the church, went to Sunday school for six years, and still attends Mass twice a month.

Polls have shown that one in five adults in the United States has read "The Da Vinci Code," and many more are familiar with its themes. George Barna, a pollster in California, says 25 percent of those who had read the book said it helped them achieve personal growth or understanding. "Few people said that reading the book had actually changed any of their beliefs," he said. "That was only 5 percent. Most people said that it essentially reinforced what they believed coming into the book."

What they believe is what Mr. Barna calls "pick and choose theology." It's a trend that Christian conservatives find scary and maddening, but that liberals tend to embrace as "big tent" inclusiveness.

"Americans by and large consider themselves to be Christian, but when you try to drill down to figure out what they believe, you find that among those who call themselves Christian, 59 percent don't believe in Satan, 42 percent believe Jesus sinned during his time on Earth, and only 11 percent believe the Bible is the source of absolute moral truth," said Mr. Barna, a conservative evangelical who regards these as troubling indicators.

Da Vinci Christianity is not so disturbing to Gregory Robbins, an Episcopalian who directs the Anglican Studies program at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver.

"When I talk to groups, they say, tell us about the Dead Sea Scrolls, the discovery of the Gnostic gospels, what went on with Constantine, was there a massive book burning by the church in the fourth century" — all elements woven into the Da Vinci plot, Mr. Robbins said.

He said he emphasizes in his talks that in its first few centuries, Christianity was not monolithic. There were Palestinian Christians, Jewish Christians, Pauline Christians who appealed to gentiles, Gnostic Christians, and Ebionite Christians who saw Jesus as merely a prophet.

Among Christians today, he said: "I have found a willingness to entertain the idea that early Christianity was very diverse. Then they're able to talk about the diversity that characterizes Christianity in the 20th century."

In the United States, many churches regarded "The Da Vinci Code" as a threat, but chose to try to educate the wayward. They set up Web sites, posted podcasts and handed out any of 46 books debunking "Da Vinci."

In developing countries — where Christianity is growing but still a minority faith in many places — the reaction from Christians was far more vehement. There were hunger strikes in India, a ban in Manila and a disclaimer before the movie in Thailand, reported The Associated Press.

Philip Jenkins, a history and religious studies professor at Penn State University, said this indicates that in the developing world, Christians still hew to the book — not "Da Vinci," but the Bible.

"In this country, even if you're a fundamentalist, reading a book is just reading a book, whether John Grisham or the Bible," he said. "If you're reading a book in India, you're probably the first generation to read, and the book has more of a sacred quality, the message carries more weight."

No hay comentarios.:

Publicar un comentario